When it looked like I’d actually unearthed a lost F. Scott Fitzgerald manuscript—a final story about his has-been Hollywood character, Pat Hobby—one of the first people I turned to was Rust.

Rust, however, was a little less enthusiastic. It turns out he was dying. For him, this was the end.

We hadn’t spoken before, but I knew who he was. He was a legend—back in the ’50s and ’60s, he made Esquire happen. Esquire, the magazine—where all the stories were. And I know, that really sounds like nothing now: “What is 'Esquire’?” “What’s ... a ‘magazine’?” “What are ‘the ’50s and ’60s’?”

But back then? If you wanted to read something fresh and new, you picked up a magazine. And if you needed high literature, or the closest commercially available thing you could hit, you read Esquire.

Rust Hills was the literary editor of Esquire at the time, and he was responsible for getting some really great writing out. He’d published Cheever, Mailer, Gaddis, Raymond Carver. I think even Richard Ford got a start from him. In any event, he dealt with the big names.

He was also a writer himself. He’d written several brilliant books of essays; I’d read them all. There also was a well-done treatise—a textbook, really—on what made a good story. His magazine was the nexus for them, so he certainly would know.

According to him, it all came down to peculiarity: the secret to great writing was having a peculiar outlook on the world. For Rust, this was the essential prerequisite you needed to be one of the big boys. Not just talent or a way with words or lots of practice or even a connection, but what you needed most was the “twist of the mind” that shows itself as a peculiar way of seeing and of speaking: “an originality of perception and utterance,” is how he put it.

You absolutely needed that. And if you had it, then sooner or later—and it might take time—it would come, no matter what anyone else would or wouldn’t do about it.

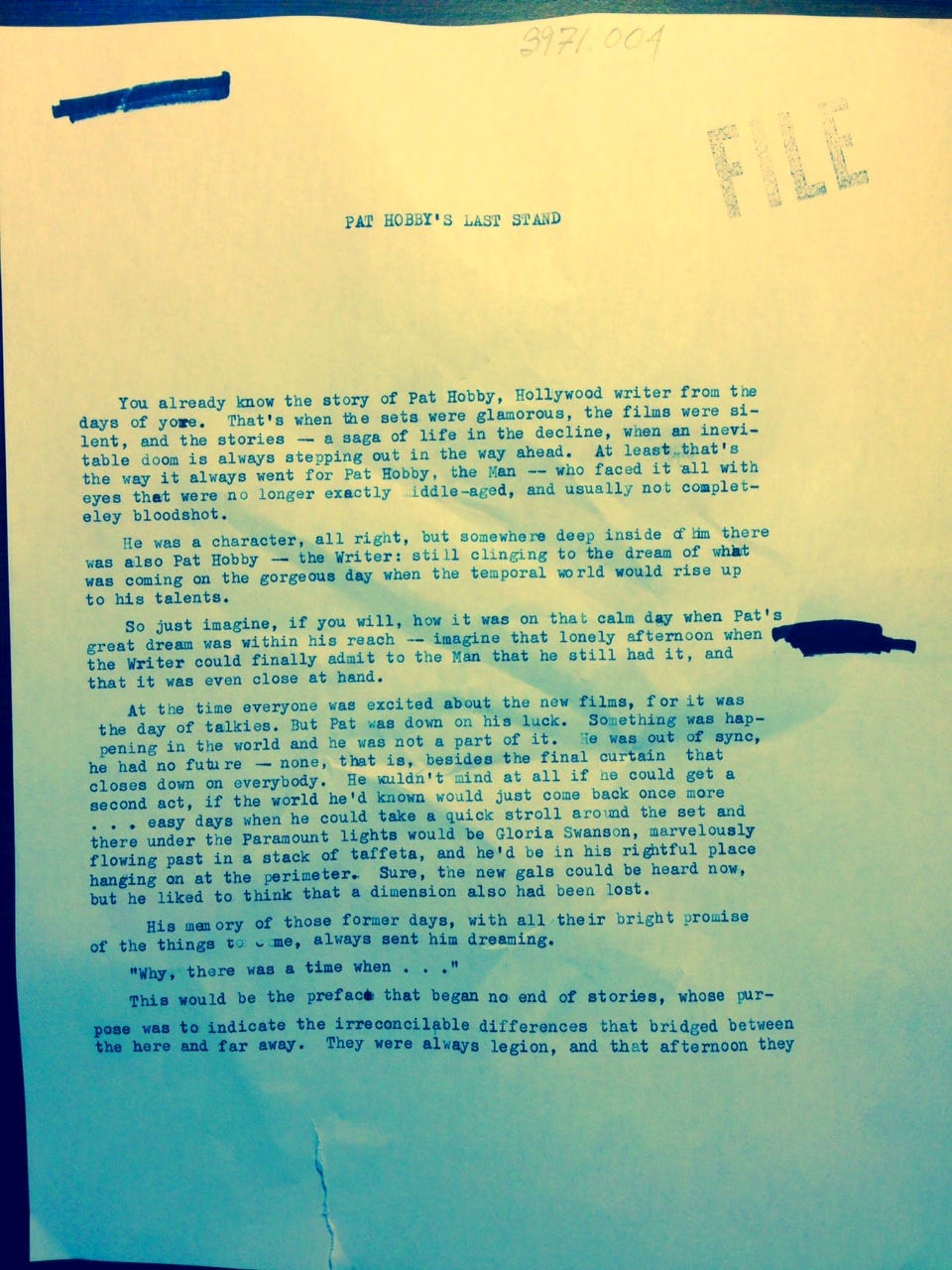

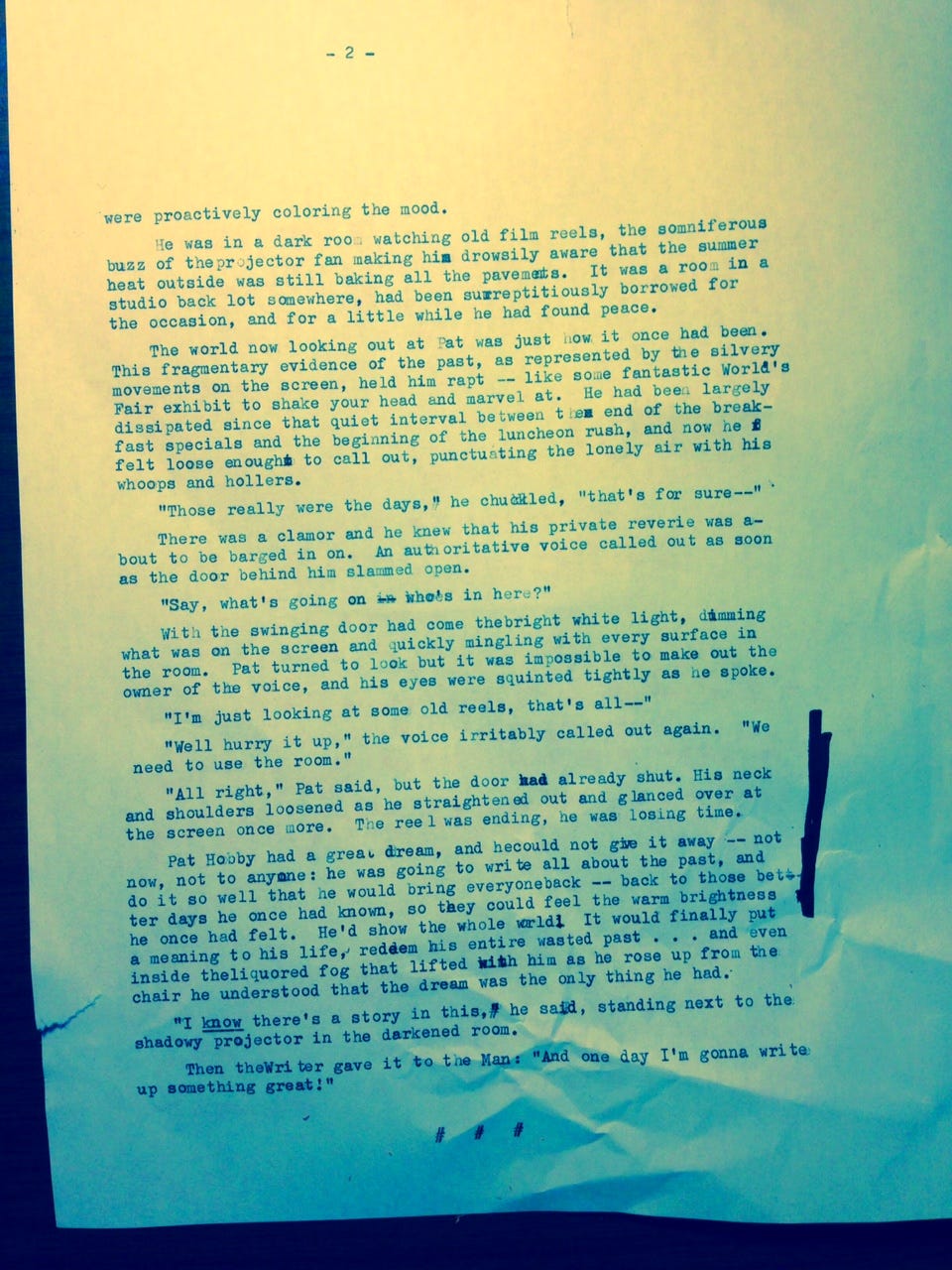

So this story, “Pat Hobby’s Last Stand,” it felt to me like literary platinum—an undiscovered classic from a forgotten archive, dug out of a black metal file cabinet in some neglected room. I’d really worked to pull every letter out of it unscathed. Ostensibly a discovery of literary archaeology, it had been one of my ways of paying workman’s dues: what I’d done was trace the words, the breaths, out from the very epoch, the center of that age—and now every time I read it, it felt to me like something from the hand of Fitz, a few folios typed out in the early jet-noir razor edge of 1940, in an LA that bustled with a new kind of brightness as the world of the silver screen was being born.

I’d even done my duty then to trace the physical places, too, all the ones that Fitzgerald haunted when he’d lived and died there: the spot where he’d resided since ’38, in a rickety old beach cottage with his girlfriend Sheilah Graham in Malibu—at the time it was the wild outback, and there was nothing there but a wended way to the fisted pummel of the sea, the cold Pacific beating down upon the rocks. Now, it was literally a grassy knoll behind a supermarket, where an abandoned shopping cart seemed to be posing for my camera helter-skelter atop the hillock. I walked out back along the home he’d once rented in West Hollywood, and another in LA proper—the former seemed to still have the original casements overlooking its inner courtyard, pitted metal handles and all; there was Musso & Frank Grill, which even now feels like one of the oldest working time machines in all of America, where the wood of the booths and the bars are rubbed smooth with the evenings of a hundred years, and the bar stewards still don proper scarlet blazers. And finally the site of the Garden of Allah, on Sunset Boulevard: once a bohemian hotel under the bowing palms, and now—well, before it was demolished—a white-bricked space age bank, where all the tellers looked up at me together in sync as I stepped around with a Fujifilm camera to document the place in the middle of the workday.

So some correspondence (on paper, through the unseen backdoor mystery of the US Mail) finally led to Rust picking up his desk phone and dialing out my number. My landline—I had one, this was right at the dawn of smartphones. And for a moment there that summer, we talked just like that on the phone.

The forgotten Pat Hobby story, as terrific and incredible a discovery as I thought it could be, that was now completely besides the point. Rust was not in any editorial position at all—he could barely breathe.

It was summer. He was in Key West, living in a bungalow in just about the heart of the key, and I could almost see the geckos bathing in the lazy sun, the white stones and bleached starfish, the blots of shade offering comfort under ragged draperies of Spanish moss.

I told him how much I appreciated his work. There was one piece in one of his books, quite fantastic but with a very dead-serious undertone, where he basically suggested a solution to everything: to unemployment, the GDP, our rate of construction, the mounting nostalgia for better days, problems in contemporary design, the loss of great landmarks, and just about every other major problem that plagued the modern world.

Because you see he knew, as we all know, that when a neat old building is torn down, anywhere in this country, it’s nearly always replaced with something grossly inferior. The new methods of construction, the new designs, the architecture, even the landscaping, all of it is a horrible counterfeit of how good things used to be. And the same with boats (look at a wooden Lyman compared to what’s new in a showroom), with roads, even with art, with absolutely everything. All the good things are neglected, left in disrepair, and eventually pulverized, and in their spot is put something shoddy and inferior. This has been going on for some time, and it’s getting worse.

It’s a hell of a problem, Rust had observed, but fortunately he’d also come up with a hell of a solution: through a big government mandate (similar to FDR’s massive machinations of the WPA), all businesses and private enterprises might work together in this country to put everything back. In other words, turn everything around, reverse course, and go the other way: unbuild everything, restore what was removed, and steadily make tomorrow look like yesterday, this week look like last week, this year look like last year—and then go back another year, a decade, and keep on going back until you’ve reached whatever golden age it is you’re looking for.

Cue the walking tour guide: “This beloved theatre stood here on town square and was a focal point up through the 1980s, until it was torn down for a CVS parking lot in 1992—and now today, we’ve brought it back.”

This, I told him, was brilliant. I told him that more people needed to know about it—his essay didn’t even show up on an Internet search, so I told him I’d surely have to write about it. The lost Pat Hobby story might even be considered an example of his idea put into concrete action.

“I’m very grateful for that,” he said weakly in a faint voice, “I’m grateful that you remember that essay, and that you’ll tell people about it.”

The call ended soon after that, and in a flash I then found out what he looked like—or at least, what he once had looked like: he’d passed away, and they printed an old photo of him in his obit in The New York Times. In the file photo you could tell that it was already shin-deep in the ’70s, in the postmodern era, but that this was a man whose sense and sensibility was locked firmly in the modern—so that whether it would be 1950 or 2050, he wasn’t giving up his deportment (or his drink and cigarette), not for anyone nor anything.

But it was over and I wouldn’t be talking to him again and I wasn’t even sure if this idea, as fantastic as it seemed, could ever be rightly implemented, anyway.

And really—right now, there was no going back to anything. Esquire was gone, magazines were over, those kind of stories were done. We were somewhere else now, somewhere far away.

After that I’d moved on, and left Pat Hobby back in that forgotten file cabinet to lie where he lies, down in the files of the far-flung past. He’s not coming back, and there won’t be any more of those pieces rediscovered. And that’s probably all right. Pat’s still there where he should be. He did what he could, and I’m very grateful for that. It’s not our job to force a direction or to even steer. That’s not the purpose of a story. It’s not like we know where anything is going, anyway, up or down, forward or not—it’s just always moving, and we’re here to talk about the ride.

Michael, while I enjoy all of your writing, this one is especially good. Keep writing.

Also, I have some things to sort out in June-mid July, but I hope I can take you guys to lunch/dinner by this time in August, if you’re interested. I’d enjoy catching up.