Only the Dead Know "Only the Dead Know Brooklyn"

On the desire to want to know all of Brooklyn, and everything that's going on, and everyone who is right here in this moment

Something big is happening in Brooklyn. I’m suddenly getting calls and taps from Brooklyn almost every day, there are energy waves coming out of it that are forming a high enough tide to be flooding out to here—at this point we’re wading in it, and we really want to know what’s going on.

Surely there’s a watershed of great musicians there. I keep running into them. Some of the most interesting record labels are based there. A few months back one of my closest friends wanted me to shut down the shop for a week so we could fly out there and hang with a band we love. The other day a buddy showed me pictures of a great new Brooklyn club that just opened, with a cedar-walled DJ booth that looked like an opulent, mid-70s Scandinavian sauna covered in ferns, and a main club space that seemed to be an authentic replica of the set used for The Haçienda in the film 24 Hour Party People—but with a better, brighter paint job. It was with maximum panache and seemed to be a place we need to scrutinize as soon as possible, since nothing like that is going on just about anywhere right now.

And when I see this stuff, I just want to know it all—consume it, walk every street and alley and know the people and their ways. Over the years I contributed to some Brooklyn sites and magazines, but never thought about it as a place to roam and know and haunt as much as I do in these weeks now. To know the tight weavings of its dense and tangled framework, feel the alleys and the curbs that interlace on the far ribbons of its constricted streets, and study the sacred silent countenance of all the people—that great unknowing mystery of it all is now a heavy constant on my mind.

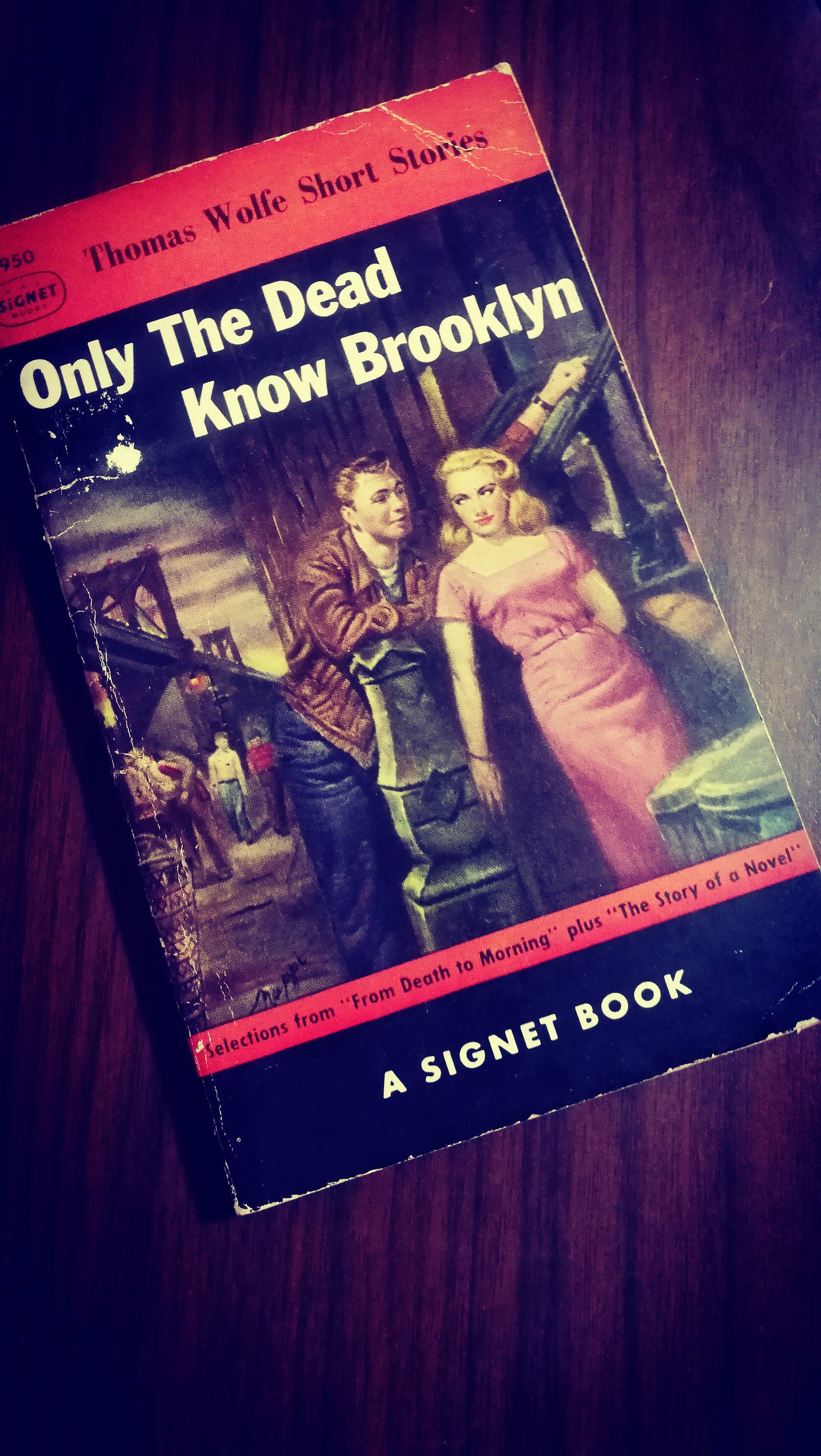

Thomas Wolfe had this same wonder about a century ago. One of his most celebrated stories, “Only the Dead Know Brooklyn,” achieves it as a kind of author’s mirror: the story’s told in the voice of a Brooklynite who’s relating his experience of meeting and talking to Wolfe on the streets, and describing it to someone off the page. Dis guy, he says, walked deh streets and looked in deh windows and wahnted to know deh entiyah city. But, of course, it’s just too big—it's Brooklyn. He laughed at the thought of it: Dis guy wants tah know all of Brooklyn? Dat ain’t even possibuh, ain’t no one ever gunnah know it troo in troo. Not in this life, they could.

I almost moved there twenty years ago. There was for sure a lot of that, everybody pouring in from the far reaches of the nation into that borough. The bloggers were all going there—to Williamsburg mostly, I guess, but it seemed that everyone who had a penchant for hipsterdom or who was starting anything with blogging or social media was hitting the trail: WordPress and Twitter people, and half a dozen promising startups that nobody remembers now, it seemed like they were all figuring out that this was suddenly the place to be. Close enough to the heart of the city, and cheap enough, and now you have a great migration going on.

One of my best friends ever, also a serious writer, had moved up above it in Astoria. We commandeered the Neptune Diner on Thanksgiving day one year like we owned it (besides the aproned Greek proprietor and a girl I brought, we were the only ones there). Back then, there was all kinds of exciting talk about art—so-and-so was working closely with David Foster Wallace, editing his new book, and such-a-such a Brooklyn publication whose editor we knew was getting all kinds of big names in it, and Web sites were being built and seemed more important than books, and people were definitely looking, and we knew this one and that … it seemed like our own domination of the billboards was only minutes away.

The luckiest of the tech nerds rocketed out fast, but everybody involved with art struggled long and hard. A lot were probably beaten into the blind unknowing pavement of the streets. A few made it, but it took ten or twenty years for the good ones who didn’t quit. Finally, now, it seems like something big’s emerging all at once.

In that day I knew a writer there, one who was very famous in the 1960s, but who’d become more or less forgotten as he grew old. His books were out of print since probably the 80s and he was only referenced here and there in academic papers, but he’d had a treasure load of insight that I went away with. Leo Gurko, I’d found and read his work and we became friends. He wrote about Wolfe in a way that no one ever had. The method, the way, what Kerouac called the longrolling American style—Gurko understood that like no other, and the way he put it was exactly how I felt was the vital direction to go in the Internet age.

Leo loved my fevered vision of a new online art, which he called apocalyptic. He was a great but frail old fellow in his nineties, living in the same lush apartment that he’d moved into sometime during the Eisenhower years. It was big enough to hold ten of the quarters all the Williamsburg kids were getting. The decor had last been updated in the early 70s; when you’d sit on the Spanish Revival furniture, orange spongy padding would ooze out of the careworn cushions. Sections of the mint and silver wallpaper were peeling from the ceiling in long, tight curls to our waists. And yet, it was the most elegant and living time machine I’d ever stepped into.

And then he died and all of that disappeared, like a tiny ripple on the East River your eyes lock onto until you just let go because it’s long melted off into everything else, and all you have is the little dream that you were thinking. “Only the Dead Know Brooklyn” might be a classic, but time has weathered that and the people who really knew it are gone. It’s not so much a point of reference anymore. It’s already been covered up a mile high with a hundred years of life and living and death and dying.

But us, we’re alive and here and we want to know what’s going on—because big things are happening in Brooklyn and even in the greater world, which is now even more enormous and unfathomable, and not even the dead will ever know it all.

In my mind's eye, that dinner at Neptune was in 2003 or so, but I just looked and it was 2001? Time sure is collapsing.

I had such a love/hate with Neptune. My go-to diner was Mini Star (RIP), at least for delivery. I'd call and the guy on the phone would know it was me. Weird special orders were no problem. One time I called during a bad flu and asked if they could get my some NyQuil and a pack of AA batteries, and he said no problem. But they were only open until 10:00, and good luck getting a seat in their tiny dining room on a Saturday morning.

Neptune was an institution, and it was open 24 hours. And my friend Rob lived next door. Food was good, but something was always slightly wrong. The prices were maybe 10% too high. The waitress was too slow. Or some part of the breakfast combo didn't work, like I wanted strawberry pancakes with eggs and bacon, and I'd have to order two complete breakfasts to get it. It was nitpicky stuff, but at 3am, I'd still end up there and deal with it. I would swear never again, and be back next Tuesday. I think that was a metaphor for just about every part of my half-decade in Astoria.

It's weird that I never felt like I fully plugged in with Astoria, and right as I was leaving for Manhattan in 2005, there was a wave of gentrification that changed the scene, like cafes with one-word names ("Bite" or "Brunch") and actual book stores and such. Looking back, I feel if I would have stayed another ten years, it would have been a much more comfortable scene. Or would it? I imagine Brooklyn is more of the same?